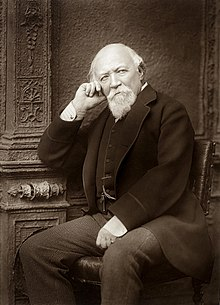

Robert Browning as a Poet

Robert Browning (1812 –1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him one of the foremost Victorian poets. Browning was famous for his dramatic monologues and commentary on social institutions. He was married to Victorian poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning. He was a true observer of the Renaissance period and he admired it. The Renaissance saw a major shift in theories of art. As “Fra Lippo Lippi” discusses, a new realism, based on observation and detail, was coming to be valued, while traditional, more abstract and more didactic forms of art were losing favor. This shifting in priorities is analogous to the shifting views on art and morality in Browning’s time. The Renaissance, like the Victorian era, was also a time of increasing secularism (see “The Bishop Orders His Tomb”) and concentration of wealth and power (“My Last Duchess”. All of these aspects make the Renaissance and the Victorian era rather similar. By talking about the Renaissance, Browning can make his cultural criticism somewhat less biting. He also gains access to a wealth of sensuous detail and historical reference, which he can then use to add vibrancy to his verse. The historical connection, furthermore, lets him talk about his place in the literary tradition: if we still appreciate Renaissance art, hopefully future generations will still appreciate Browning’s poetry.

I also want to say that Browning aspires to redefine the aesthetic. The rough language of his poems often matches the personalities of his speakers. Browning uses colloquialisms, inarticulate sounds (like “Grr”), and rough meter to portray inner conflict and to show characters living in the real world. In his earlier poems this kind of speech often accompanies patterned rhyme schemes; “My Last Duchess,” for example, uses rhymed couplets. The disjunction between form and content or form and language suggests some of the conflict being described in the poems, whether the conflict is between two moral contentions or is a conflict between aesthetics and ethics as systems. Browning’s rough meters and unpoetic language test a new range for the aesthetic.

Here one more remarkable point is that Women, particularly for the Victorians, symbolize the home the repository of traditional values. Their violent death can stand in for the death of society. The women in Browning’s poetry in particular are often depicted as sexually open: this may show that society has transformed so radically that even the domestic, the traditional, has been altered and corrupted. This violence also suggests the struggle between aesthetics and morals in Victorian art: while women typically serve as symbols of values (the moral education offered by the mother, the purity of one who stays within the confines of the home and remains untainted by the outside world), they also represent traditional foci for the aesthetic (in the form of sensual physical beauty); the conflict between the two is potentially explosive. Controlling and even destroying women is a way to try to prevent such explosions, to preserve a society that has already changed beyond recognition.

Actually he more known to be mark of seasons as his writing influenced with the part of stability and now talking about his work so first look on In March 1833, Pauline, a fragment of a confession was published anonymously by Saunders and Otley at the expense of the author, the costs of printing having been borne by an aunt, Mrs Silverthorne. It is a long poem composed in homage to Shelley and somewhat in his style. Originally Browning considered Pauline as the first of a series written by different aspects of himself, but he soon abandoned this idea. The press noticed the publication. W.J. Fox writing in the The Monthly Repository of April 1833 discerned merit in the work. Allan Cunningham praised it in The Athenaeum. However, it sold no copies. Some years later, probably in 1850, Dante Gabriel Rossetti came across it in the Reading Room of the British Museum and wrote to Browning, then in Florence to ask if he was the author. John Stuart Mill, however, wrote that the author suffered from an "intense and morbid self-consciousness". Later Browning was rather embarrassed by the work, and only included it in his collected poems of 1868 after making substantial changes and adding a preface in which he asked for indulgence for a boyish work.

His major works:

♣ Pauline: A Fragment of a Confession (1833)

♣ Paracelsus (1835)

♣ Strafford (play) (1837)

♣ Sordello (1840)

♣ Bells and Pomegranates No. I: Pippa Passes (play) (1841)

♣Bells and Pomegranates No. II: King Victor and King Charles (play) (1842)

♣ Bells and Pomegranates No. III: Dramatic Lyrics (1842)

♣ "Porphyria's Lover"

♣ "Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister"

♣ "My Last Duchess"

♣ "The Pied Piper of Hamelin"

♣ "Count Gismond"

♣ "Johannes Agricola in Meditation"

Here I want to put few lines of his work,

“One who never turned his back, but marched breast forward,

Never doubted clouds would break,

Never dreamed, tho’ right were worsted, wrong would triumph,

Held we fall to rise, are buffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake.

~ Epilogue, Browning

In 1834 he accompanied the Chevalier George de Benkhausen, the Russian consul-general, on a brief visit to St Petersburg and began Paracelsus, which was published in 1835. The subject of the 16th century savant and alchemist was probably suggested to him by the Comte Amédée de Ripart-Monclar, to whom it was dedicated. The publication had some commercial and critical success, being noticed by Wordsworth, Dickens, Landor, J.S. Mill and others, including Tennyson (already famous). It is a monodrama without action, dealing with the problems confronting an intellectual trying to find his role in society. It gained him access to the London literary world.

As a result of his new contacts he met Macready, who invited him to write a play. Strafford has performed five times. Browning then wrote two other plays, one of which was not performed, while the other failed, Browning having fallen out with Macready. In 1838 he visited Italy, looking for background for Sordello, a long poem in heroic couplets, presented as the imaginary biography of the Mantuan bard spoken of by Dante in the Divine Comedy, canto 6 of Purgatory, set against a background of hate and conflict during the Guelph-Ghibelline wars. This was published in 1840 and met with widespread derision, gaining him the reputation of wanton carelessness and obscurity. Tennyson commented that he only understood the first and last lines and Carlyle claimed that his wife had read the poem through and could not tell whether Sordello was a man, a city or a book.

Browning's reputation began to make a partial recovery with the publication, 1841–1846, of Bells and Pomegranates, a series of eight pamphlets, originally intended just to include his plays. Fortunately his publisher, Moxon, persuaded him to include some "dramatic lyrics", some of which had already appeared in periodicals.

References:

Irvine, William, The book, the ring, & the poet; a biography of Robert Browni, New York, McGraw-Hill 1974.

Ryals, Clyde de L., The life of Robert Browning: a critical biography, Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell, 1993.

Words:1186

No comments:

Post a Comment